This is the third in a series of four blog posts that discuss discrimination and harassment in cyberspace, its perpetrators, and its consequences. The first post, “Identity and Ideas,” is available here. The second post, “Anonymity and Abuse,” is available here, with a short addendum here.

Suppose you run a website, and the anonymous commenters on your site start hurling racial and sexual slurs at someone they’ve targeted. Or suppose you start a thread in an online forum, and you notice that the commenters are engaging in identity-based harassment of someone–either a participant in the thread or otherwise. Or suppose you didn’t start the thread, but you went to the site and you read it.

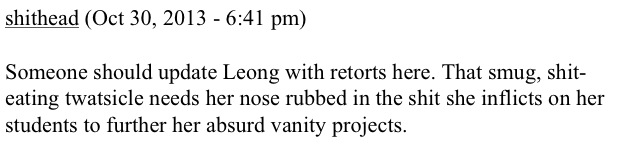

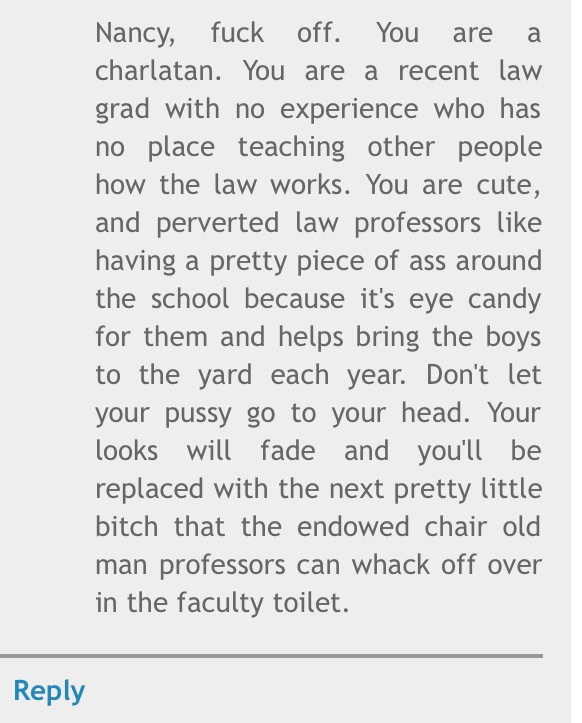

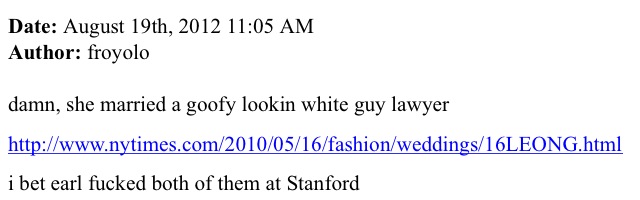

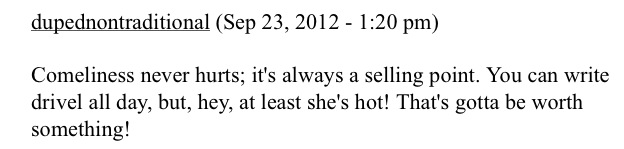

For anyone new to this series, when I talk about identity-based harassment, I’m talking about comments like the ones below, which are all comments about me:

Or this:

Or this:

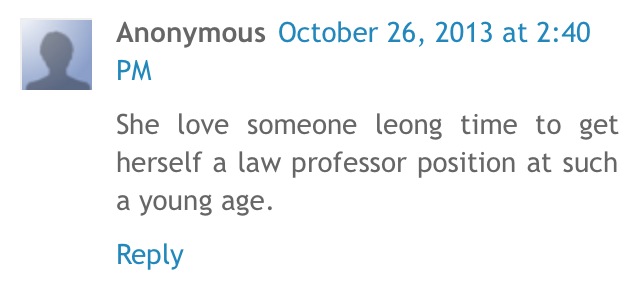

Or this:

I confess that I am not particularly concerned with what “shithead” and “froyolo” think of me. Their comments, however, helpfully provide a concrete context for my opening questions. Suppose you encountered these comments. What should you do? Framed more broadly, what are the social and legal responsibilities triggered by identity-based online harassment?

I’ll start with the social responsibilities. These are things you should do, not (necessarily) because they’re legally required, but as part of being a good person. My definition of being a good person includes actively opposing racism, misogyny, and other forms of identity-based abuse. If you disagree with this definition, I’m afraid the rest of this post may be difficult for you.

Here are some social responsibilities: If you start a website and it turns into a rancid cesspool of racist and misogynistic vitriol, it’s your responsibility to clean it up. If you start a thread and the comments turn ugly, it’s your responsibility to intervene. And if you read a thread and see the commenters abusing someone, it absolutely is your responsibility to call out the abuse.

Opposing racism and sexism is inconsistent with passivity in the face of online abuse. Nobody gets to sit on the sidelines. If you administer a website, you don’t get to sit back and play clockmaker god while your creation devolves into a racist monstrosity. If you start a thread that turns into a misogynistic cybermob, you don’t get to shrug your shoulders and look away. Or, to put it differently, of course you can do these things, but you can’t do them and still hold tight to your moral authority. Your privilege–the privilege that you enjoy because the comments aren’t about you–doesn’t entitle you to blameless passivity. I’m reminded of this message from a law firm partner to an administrator of the infamous AutoAdmit website: “We expect any lawyer affiliated with our firm, when presented with the kind of language exhibited on the message board, to reject it and to disavow any affiliation with it. You, instead, facilitated the expression and publication of such language.” In other words, we have a responsibility to act when we see identity-based online harassment. This is particularly true for attorneys, and even more so for attorneys who represent vulnerable populations. (I’ll have more to say about this in my next and final post.)

I am well aware that what I am proposing is a significant departure from current online norms. Most people don’t call out racist and sexist comments–even people who would never make such comments themselves–because they prefer not to have to deal with the consequences. To justify their passivity, they hide behind platitudes, like “there will always be assholes on the Internet,” or “don’t feed the trolls,” or simply “it’s not my problem.” But this is exactly my point. You can decide it’s not your problem, or you can oppose racism and sexism. You can’t do both.

I am also well aware that some of the things I posit as social responsibilities are arguably difficult to do. For example, website administrators may find it burdensome to monitor comments. But plenty of websites–from the New York Times to Jezebel—do manage to maintain a commenting environment largely free of targeted racism and misogyny, which suggests that the problem is not ability but effort. And even websites noted for awful comments are making progress in the right direction. Moreover, technological tools are in the works that can make the task of moderation easier for everyone. And if it’s really that difficult for a particular website to eliminate identity-based online harassment, perhaps that site should simply close down its comments.

Likewise, individuals may find it psychologically burdensome to call out identity-based online harassment, either in threads they started or in threads they read. Obviously there are practical limits–everyone has only so much bandwidth to call out harassment–but I think it should be a shared burden, distributed evenly among everyone. If you have the psychological wherewithal to start a thread–or read one–then surely you can also write a one-sentence comment calling out identity-based harassment. It’s true that lengthy, detailed responses, might, in some circumstances, perpetuate a tornado of race- or gender-based abuse. But even a short anonymous statement such as “This is sexist and I disagree” has many positive benefits.** Such a statement lets the target know he or she is not alone. It forces other readers to acknowledge the comments for what they are. And sometimes it may shame the authors of such comments into silence.

Depending on the circumstances, calling out harassment might sometimes require a more involved response–including, for example, contacting the target to see whether he or she has a preference about the way the harassment should be handled. The larger point is that good people don’t sit and scroll and sip their coffee and watch an online mob savage someone else’s life without doing anything about it.

Some people become enraged at the mere notion of moderating or closing down comments. Some people become defensive at the idea that they have an affirmative duty to intervene in instances of identity-based online harassment. But the alternative is to require women and people of color (among other marginalized groups) to bear a vastly disproportionate burden. My previous posts have explained why, if we really care about having a robust marketplace of ideas, this disparate burden should be unacceptable to us.

On that note, I’ll turn to the legal implications. Everything I have mentioned to this point involves private actors and therefore doesn’t implicate the First Amendment. But I also think that–following the model of Title VII–Congress could legislate narrowly to proscribe online behavior whose purpose is to harass a specific person on the basis of traditionally protected categories including but not limited to race, gender, national origin, and religion. As I have already mentioned, Title VII proscribes such targeted harassment in the workplace. Cyberspace, of course, is not the workplace. But it is a space where many of us do a lot of our work, and for many of us it’s a space that’s inextricable from our professional identities.

Other scholars have already devoted a great deal of time and careful thought to identity and online harassment. In a previous post, I mentioned Saul Levmore and Martha Nussbaum’s anthology The Offensive Internet, which includes several essays that address these themes. Daniel Solove’s outstanding monograph The Future of Reputation examines privacy, reputation, rumor, and freedom in cyberspace. Jerry Kang’s work “Cyber-Race” examines the way that racial identity functions in online ecosystems. And Danielle Citron emphasizes the notion of “Cyber Civil Rights“–the idea that identity-based online harassment “ought to be understood and addressed as a civil rights violation.” I won’t retread ground that other commenters have already covered. As a scholar of identity and discrimination, however, I would like to add an illustration of why we should think of identity-based harassment as a civil rights violation. Consider the following three statements:

Statement One: “Leong didn’t get that law professor position on her own merit.”

Statement Two: “Leong slept with someone to get herself a law professor position.”

Statement Three:

All three statements are false and defamatory. Whether they are actionable is, of course, a different question, as there are various doctrinal and practical obstacles to defamation suits. But my focus here is on whether the doctrinal mechanism, at least in theory, captures the injury. The idea behind defamation nicely captures the problem with the first statement. It’s a false statement that, if believed, would damage my reputation. Defamation falters, however, with respect to the second statement. It is defamation, but there’s more to it than that. The statement no longer treats me as an individual, but instead applies offensive stereotypes about women’s presumed incompetence. I simply could not have gotten that position on my own merit, I must have slept with someone, because however else could a mere woman get a law professor position? And the third statement adds a racial dimension to the prior injuries of defamation and misogyny by very cleverly coupling my last name with a phrase that Asian women supposedly say, according to some white guys who make movies. Asian women are stereotyped as sexually available: that’s why there are books like this, and songs like this atrocity, and documentaries like this, and AMA performances like this one.

It’s a simple point, but worth repeating: defamation doesn’t address the identity-based harms suffered by historically marginalized groups. And this is why we need a civil rights regime for the Internet, not unlike the one we have in the workplace: to capture the unique identity-based harms that take place here. Ignoring the fact that some identity groups enjoy greater privilege ignores reality. As Louis CK explains, “I’m a white man! You can’t even hurt my feelings.”

My final post will discuss the various avenues that people targeted by identity-based online harassment can pursue.

* I have chosen not to link to, or to identify, the sources of the material I reference in this post because I do not want to drive traffic to websites that tolerate racial and sexual harassment. If you would like more information, please feel free to contact me.

**UPDATE: A thoughtful reader suggested the wording “This is sexist and unacceptable.” I like that suggestion very much, and probably more than my original wording.

– Nancy Leong